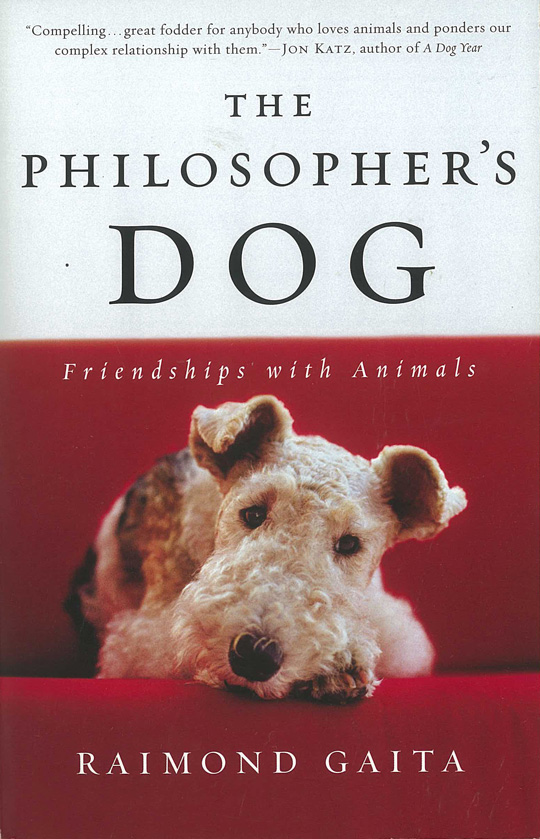

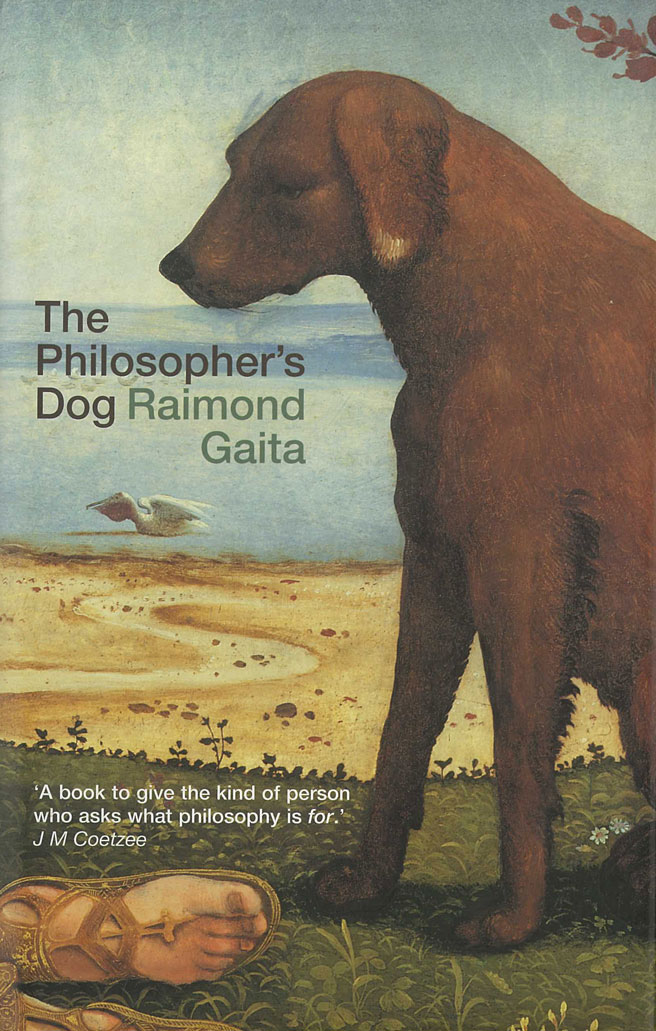

In this beautifully written book Raimond Gaita tells inspirational, poignant, sometimes funny but never sentimental stories of the dogs, cats and cockatoos that lived and died within his own family. He asks fascinating questions about animals: Is it wrong to attribute the concepts of love, devotion, loyalty, grief or friendship to them? Why do we care so much for some creatures but not for others? Why are we so concerned with proving that animals have minds? Reflecting on these questions, and drawing on the ideas of Descartes, Wittgenstein and J.M. Coetzee, Gaita pleads that we ask ourselves what it means to be creatures of ‘flesh and blood.’ He discusses mortality and sexuality, the relations between storytelling, philosophy and science and the spiritual love of mountains. An arresting and profound book, The Philosopher’s Dog is a triumph of both storytelling and philosophy. The Routledge Classics edition includes a substantial new introduction and afterword by the author. (Routledge)

SHORLIST

SHORLIST

NOMINATED

This Routledge Classics edition includes a substantial new introduction and afterword by the author.

“Routledge classics contains the very best of Routledge publishing over the past century or so, books that have by popular consent become classics in their fields . . . this series makes available in attractive affordable form some of the most important works of modern times”. (Routledge)

In everything that Raimond Gaita writes we sense a generous heart at work, as well as a lucid intelligence. The Philosopher’s Dog is a book to give to the kind of person who asks what philosophy is for.

A rich and exciting book.

A wonderful book . . . you should buy two copies – one for yourself and one for your dearest friend . . . there are few books that achieve, as this one does, a unity of head and heart . . .

[Gaita] soars into a rich and dense meditation on the nature of our moral connections, with one another as well as with animals, insects and plants. . . . Ever true of philosophy…it poses tough questions. That is its job. To pose them in such an exhilarating way is rare indeed. . Rarely are the personal and the philosophical so deeply entwined. Yet the book is lightened by Gaita’s humour and the genuine affection for the animals he writes about.

One of the richest books about animal/human interactions this critic has encountered . . . an exquisite book in which one man has grappled not only with the question of what separates him from the animals but also with the realization that he cannot fully know the answer.

Despite the sensitivity of his narrative writing, when he’s describing the pain of a sick animal, or the devotion of a dog to a lonely child, Gaita is foremost an unapologetic thinker . . . I was surprised how much I took from this book, not just from the lyricism of the literary content . . . There’s a great deal in The Philosopher’s Dog that is provocative and liberating.

Rai Gaita is a dog-lover, a philosopher and a gifted, sensitive writer. In this immensely readable and enjoyable book, he mixes the personal with the philosophical and the anecdotal with the profound to produce a series of illuminating reflections on what it means to be a creature and, more importantly, what it means to be fully human. It should not be missed by anyone who still hopes to find in the works of philosophers things that are both interesting and important.

I find it hard to think of a more readable book of genuine philosophy in the genre staked out by Wittgenstein, Rush Rees (another dog man) and Peter Winch: the Cambridge, Swansea and London triangle. Once again, Gaita shows himself a doyen of this genre. His distinctive voice weaves together, or teases apart, texts, contexts and textures Someone writing so accessibly and non-trivially deserves more than the distinction of starting a new fashion in book titles.

The book possesses a peculiar charm and at the same time displays a welcome, sinewy toughness in its thinking . . . Gaita is remarkable in the fearlessness with which he wears his heart on his sleeve. . . He is dealing with high matters here, some of the highest, indeed, – how to live decently, how to behave toward our fellow men, how to treat animals . . . like the Wittgenstein of Philosophical Investigations, [Gaita]recognises that language when employed poetically can be a web in which to catch things that seem, paradoxically, beyond expression.

Raimond Gaita has written a wonderfully humane book, clearly formulated and grounded in its subject-matter while achieving a purity and simplicity of voice rarely achieved in philosophy.

The latest volume from the author of Romulus, My Father is an enchanting and pellucid mediation on animals with particular emphasis on Raimond Gaita’s family pets. It’s a surprisingly easy blend of philosophy, storytelling and literary criticism. It reads like a book of parables without being at all tendentious of coercive. The Philosopher’s Dog is thoughtful, touching and utterly admirable.

Articulates and attitude of grateful respect without ever indulging in sentimental fantasies. An outstanding exercise in seeing things clearly

Writing to make the soul sing.

Beautiful stories . . . Gaita is a subtle and sensitive thinker who is full of sharp and valuable observations.

Gaita is a wonderful storyteller. He observes his animals precisely. The Philosopher’s Dog is an unusual book of philosophy – it is brilliantly written and filled with marvellous stories. Even so it is a well-grounded and precise philosophical analysis of the foundations of our ethics.

Clever an energetic – Gaita’s ability to spin philosophy from his tales of everyday life is remarkable.

Raimond Gaita’s passionate mixture of memoir and philosophy is indeed about relationships between people and animals, yet its conclusions – and even its byways – are astonishing. Ultimately, The Philosopher’s Dog is an exploration of love and recognition.

Extract

Raimond Gaita

The Philosopher’s Dog

“Sometimes on cold mornings my father found bees lying on the grass outside the hive, to all appearances quite dead. He would collect them in the palm of his hand and take them into the kitchen where he placed them on the table. Then he would take an electric bulb and move it to and fro, fifteen or so centimetres above them, so they would be warmed by it but not harmed by a concentration of heat on any part of them. When I first saw him do this I was moved by his attentive tenderness and entranced by its results. Gradually signs of life appeared. Legs twitched ever so slightly that one wondered whether it had really happened, and then more surely so that I knew that the bees had been restored to life by this gentle miracle-worker. Soon they struggled to turn right side up, and when they succeeded, often with a little help from us, and it looked as though they were ready to fly, we took them outside. My father brushed them from the table with the side of an open hand into the cupped palm of the other, as one does breadcrumbs, but gently, and we took them outside where they flew away. He never told me why they were lying outside the hive. I don’t know if he knew or had a theory about it. It occurred to me that they were perhaps driven out of the hive by the other bees and that each morning we collected and brought the same bees to life.

My father’s attitude to his bees moved me and transformed my sense of the insect world. Over the years I reflected on it, but not because it alerted me to new facts about bees, nor because it made me wonder whether the facts I knew required me to bring my conduct towards insects under principles I had hitherto applied only to my conduct towards animals. He taught me what compassion for an insect could be and what behaviour to them could mean. He taught me by his example, but I do not think of his example as having introduced me to something I could assess independently of the authority with which it moved me

“The white patch in a dark blue sky changed shape as he turned or rose or descended. Often in winter the grass was also white, thick with frost that stayed until ten and even eleven in the morning. In summer, it grew high and yellow and was especially beautiful in the late afternoon if the wind joined with the sun to transform entire paddocks into waves of moving grass, golden and tipped with silver. The thrill of seeing him in that landscape, against that sky, imprinted an image on my mind that is as vivid now as the sight of him was more than forty years ago. He was Jack, our cockatoo, and he was following me to school, flying a bit, then sitting on the handlebars of my bike before flying some more.

Jack was much more my father’s pet than mine. In fact, I’m not sure that I should say he was mine at all. We lived together on terms he dictated, indifferent to my need to possess him, giving or withholding affection as he pleased. Nonetheless, he was a great joy to me and never more so than when he followed me to school. When he sat on my handlebars I felt we were friends. I even dared hope that we were comrades. But back at home, in the evening of the same day that he followed me to school, if I moved to stroke his crest he was as likely as not to bite me just because he felt like it.

Jack flew free and had the run of the house. He slept on the kitchen door on which he made himself at home by eating parts of it and the adjacent wall away. Almost every morning he would climb down from his door and come into the bedroom in which my father and I were sleeping. The sound of his beak and claws alternately scraping on the kitchen door as he climbed down, and of him trying to open the bedroom door by pushing it with his head and retreating as it closed on him, usually woke us. But if my father remained asleep, or if he pretended to be asleep, Jack would perch on the bedstead until he opened his eyes. He would then jump under the blankets, poking his head out occasionally to kiss my father.

How does a cockatoo kiss? Like this. He puts the upper part of his beak onto your lips and, nibbling gently, runs it down to your lower lip, all the while saying, ‘tsk tsk tsk’. That, at any rate, is how Jack did it to my father, with unmistakable tenderness. My father would stroke him, under his wings, under his beak and on his chest and stomach. Sometimes he would cup his hands around Jack’s head and return his kisses. The same sound—tsk, tsk, tsk—came from under the blankets together with an occasional a squawk, sometimes of pleasure and sometimes of sudden but slight pain as my father inadvertently hurt him. Never, however, did I hear a squawk of fear or even anxiety, never anything that that suggested Jack’s trust of my father was qualified in the slightest degree.”

“Before Jack, and more deeply than Jack, Orloff was my first animal friend. He was a black greyhound cross, taller and more solid than most greyhounds. We inherited him from the people who lived at Frogmore before us. If I ever knew how old he was I have now forgotten, but the strength in his muscular, body and the speed with which he ran after rabbits and almost always caught them, makes it certain that he was still quite young. If he came across a fence while chasing rabbits, he would angle his body to the side so that he could pass between two strands of wire without noticeably slowing down.

My childhood was troubled. Early in it my mother left my father, repeatedly returned and left again. Though he loved me profoundly and though I never doubted it, my father was not a physically affectionate man, so I turned to Orloff for warmth and comfort. Probably I would have done so even if my father were different, for I suspect there are ways in which a dog can come closer than a man to satisfying a child’s unfulfilled need of a woman’s touch.

For a time during our life in the country my father worked nightshift and I was alone at night in our dilapidated farm house. Miles from the nearest town and a quarter of a mile from the nearest homestead, it had no electric lighting and creaked ominously in the wind. To cope with my fear, I took Orloff to bed with me, grateful for his reassuring presence, but disappointed that he showed no interest in the stories that I listened to on the wireless until I fell asleep.

When I went to school six kilometres way Orloff often accompanied me part of the way and he would be there, the same distance from the house, when I returned. Mostly I rode to school on my bike, but occasionally a neighbouring farmer would drive me. As I walked from the junction of the road and the rough track to our house Orloff would bound up to greet me with such enthusiasm that he would knock me over. Lying there in the long grass with him standing over me, legs astride my chest, licking me and making affectionate noises and wagging his tail so furiously that his entire body swayed with it, I felt he was my closest and truest friend and I loved him.